The project about Soviet Union repression against civilians was presented in April 2021 at the international scientific conference as an interactive 3D exhibition in three languages and published in the Ukrainian popular science magazine Local History.

The project entitled "Under the Pressure of the Totalitarian Regime" is dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the secret operation "North" - the largest religious repression in the USSR, against members of the peaceful organization of Jehovah's Witnesses. It explores the period from 1951 to the present day and portrays the victims of repression. Their difficult past is reflected in the physiognomy of the portraits, forming what is called "steel faces" - people who resisted the system, preserved humanity, defended their rights, freedom of conscience, and religion, and survived the entire totalitarian empire, which seemed eternal. It is extremely important for modern society to observe this imprint this rare moment allows us to comprehend the most important human values without which strong peace is impossible.

This is a one-of-a-kind project that covers: the holodomor, political and religious repressions, and the slave-like exploitation of children in the format of a documentary portrait photo project. Two photographers, Egon Ligi (Estonia) and Viorel Gurița (Moldova) have joined my photo project. The project presents living eyewitnesses and their thrilling biographies from three European countries. The photos illustrate people of different ages, as a result, the stories of migrants are very diverse. The viewer can clearly understand what it meant to fall under the steel arm of Soviet repression through the eyes of people of various ages. Additionally part of the photo story includes people who were on the side of the Soviet government.

In collaboration with historical scholars, we have thoroughly researched the history of those events with the help of declassified KGB archives of Ukraine, Moldova, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. As a result, we were able to outline the new findings, which shed more light on this deportation, specifically we determined that the operation "North" is the largest religious deportation in the history of the USSR.

Also, there are more than a hundred authentic photos that were collected from 4 European countries, which tell us about the places, work, social conditions, and life of exiles.

The project involved: software developers, 3D modelers, visualizers, painters, photographers, designers, directors, videographers, artists, composers, interpreters, historians, philologists, journalists, sound directors, and many others.

Also, there are more than a hundred authentic photos that were collected from 4 European countries, which tell us about the places, work, social conditions, and life of exiles.

The project involved: software developers, 3D modelers, visualizers, painters, photographers, designers, directors, videographers, artists, composers, interpreters, historians, philologists, journalists, sound directors, and many others.

This set of media materials will be available on the following website

Tadey Horchynskyi (87), photographed at his home in the town of Rozdil, Ukraine, from where he was deported to Siberia at the age of 16.

At night armed soldiers broke into Horchynskyi`s house. Although his family was wealthy, the soldiers did not allow them to take what they needed, and confiscated all their property "I only had a pillow and a blanket in my hands."

Upon Horchynskyi`s arrival, he was forced to sign a document from the MGB special commandant's office that he had come to Siberia "forever," after which he was housed in barracks with 69 other exiles. Horchynskyi says: “I was assigned to a molewood forest rafting on the Oka River. It was a dangerous job, and I couldn't swim, but no one cared. Once the whole raft was blocked. Approaching the traffic jam, my partner moved the log with a hook, and immediately the 6-meter traffic jam spread along the river. My partner managed to get to the shore, but I had no chance. I raced downstream, standing on a wide log that spun underfoot. In order not to perish, I forced the dredge into the tree with all my strength and drove for a whole kilometer like a rudder until I came ashore... Additionally, we were plagued by swarms of mosquitoes that could bite us to death. To protect myself, I would cover my face with a layer of cup grease, and at home, I would use a knife to scrape off the cup grease along with the mosquitoes from my face."

At night armed soldiers broke into Horchynskyi`s house. Although his family was wealthy, the soldiers did not allow them to take what they needed, and confiscated all their property "I only had a pillow and a blanket in my hands."

Upon Horchynskyi`s arrival, he was forced to sign a document from the MGB special commandant's office that he had come to Siberia "forever," after which he was housed in barracks with 69 other exiles. Horchynskyi says: “I was assigned to a molewood forest rafting on the Oka River. It was a dangerous job, and I couldn't swim, but no one cared. Once the whole raft was blocked. Approaching the traffic jam, my partner moved the log with a hook, and immediately the 6-meter traffic jam spread along the river. My partner managed to get to the shore, but I had no chance. I raced downstream, standing on a wide log that spun underfoot. In order not to perish, I forced the dredge into the tree with all my strength and drove for a whole kilometer like a rudder until I came ashore... Additionally, we were plagued by swarms of mosquitoes that could bite us to death. To protect myself, I would cover my face with a layer of cup grease, and at home, I would use a knife to scrape off the cup grease along with the mosquitoes from my face."

For 14 years, such ones as Horchynskyi could go to the market in the town of Zima only once a week under the supervision of an armed convoy to purchase essential goods.

Horchynskyi spent 14 years in exile and in 1967 he returned to Ukraine. After the collapse of the USSR, he received a rehabilitation certificate as a victim of repression. In October 2021, Tadey died.

Horchynskyi spent 14 years in exile and in 1967 he returned to Ukraine. After the collapse of the USSR, he received a rehabilitation certificate as a victim of repression. In October 2021, Tadey died.

Olha Kosach (84), holds scissors in her hands as an attribute of her work in Siberia.

In 1951 Olha Kosach and her family were deported from the village of Rozvadiv. "At that time, I was a fourth-grade student. I remember how that night, a soldier helped me get my books from the shelf and said, 'You'll go to school there too.' There were 52 people, including a baby girl named Myroslava, in the freight car. She was 11 months old, and I was 11 years old. Myroslava lay in a cradle that was placed on a chest. I played with her and rocked her all the time; she was like a doll to me, so the two-week journey to Siberia wasn't sad for me."

After arriving in Siberia, Olha and her family were placed in a barrack from a converted stable where bedbugs constantly disturbed them. Learning at school was difficult because she did not understand Russian. "At 14, I started working in a woodworking shop for minors. With the other children, I sawed boards for boxes". After that, Kosach mastered sewing and worked in a factory studio. She recalls: “My honesty and success in work began to be noticed by the management. For this, I received respect from all employees and management."

In 1967, Kosach returned to Ukraine.

In 1951 Olha Kosach and her family were deported from the village of Rozvadiv. "At that time, I was a fourth-grade student. I remember how that night, a soldier helped me get my books from the shelf and said, 'You'll go to school there too.' There were 52 people, including a baby girl named Myroslava, in the freight car. She was 11 months old, and I was 11 years old. Myroslava lay in a cradle that was placed on a chest. I played with her and rocked her all the time; she was like a doll to me, so the two-week journey to Siberia wasn't sad for me."

After arriving in Siberia, Olha and her family were placed in a barrack from a converted stable where bedbugs constantly disturbed them. Learning at school was difficult because she did not understand Russian. "At 14, I started working in a woodworking shop for minors. With the other children, I sawed boards for boxes". After that, Kosach mastered sewing and worked in a factory studio. She recalls: “My honesty and success in work began to be noticed by the management. For this, I received respect from all employees and management."

In 1967, Kosach returned to Ukraine.

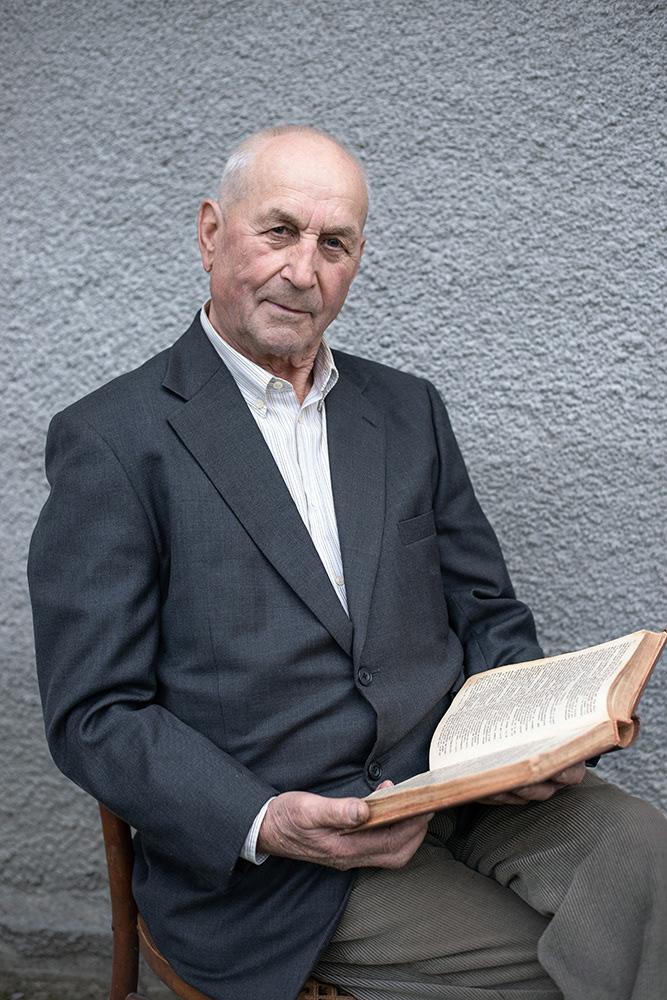

Ivan Humeniak (92), photographed in his house in Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine, from where he and his parents were exiled to Siberia.

Today, Humeniak recalls how his family first fell under the brutal hand of the Gestapo. After WWII, they continued to be persecuted by the Communists.

In 1951, at 3 am, six armed MGB men broke into their house. "At their demand, we handed over our documents. We all sit down at the table, and nearby a gas lamp is burning. The head of the MGB gives us a sheet of paper and says, 'Sign here that you renounce your faith' and my father and I reply, 'How can we renounce God when He gives us harvest, when He provides everything necessary for life?' Then this officer angrily shouts, 'Search!'"

Humeniak and his family were put into a freight car, which they traveled to Siberia for about 3 weeks. He was then 22. "We were accommodated in barracks when it became very cold in the barracks, we dug ourselves dugouts and lived in them until we built a log cabin".

In Siberia, on the outskirts of the settlement of Veselyi, Humeniak built a secret "bunker" in the taiga, where he produced Bible literature banned by the Soviet authorities. During the night he managed to print 1000 pages. This activity exposed him to the possibility of imprisonment for up to 25 years. He says: "I cleared the trunk of the withered birch through; it provided a constant circulation of fresh air in the bunker, and the entrance was masked by a small spruce. At night I typed, and during the day I worked cutting down the forest."

Humeniak spent 14 years in exile. In 1967 he returned home. In July 2021, Ivan died.

In 1951, at 3 am, six armed MGB men broke into their house. "At their demand, we handed over our documents. We all sit down at the table, and nearby a gas lamp is burning. The head of the MGB gives us a sheet of paper and says, 'Sign here that you renounce your faith' and my father and I reply, 'How can we renounce God when He gives us harvest, when He provides everything necessary for life?' Then this officer angrily shouts, 'Search!'"

Humeniak and his family were put into a freight car, which they traveled to Siberia for about 3 weeks. He was then 22. "We were accommodated in barracks when it became very cold in the barracks, we dug ourselves dugouts and lived in them until we built a log cabin".

In Siberia, on the outskirts of the settlement of Veselyi, Humeniak built a secret "bunker" in the taiga, where he produced Bible literature banned by the Soviet authorities. During the night he managed to print 1000 pages. This activity exposed him to the possibility of imprisonment for up to 25 years. He says: "I cleared the trunk of the withered birch through; it provided a constant circulation of fresh air in the bunker, and the entrance was masked by a small spruce. At night I typed, and during the day I worked cutting down the forest."

Humeniak spent 14 years in exile. In 1967 he returned home. In July 2021, Ivan died.

Vasyl Livyi (71), in a favorite room of his house and remembers the music he played in an underground brass band. He still has underground recordings of their orchestra's 1967 music.

In the spring of 1951, MGB officers took 7-month-old Livyi and his family from the village of Pidhirtsi, Ukraine, to Siberia. He was transported for 2 weeks by boxwagon to the village of Tsentralnyy Khazan, Irkutsk region. "During the journey, my mother fed me chicory because there was no milk."

A year after arriving in Siberia, his father was arrested as an ideological opponent and given 25 years of imprisonment. His mother was left without a husband and with three children. "For the first 5 years, I had no idea what my father looked like; I had never even seen a photograph of him. Everything I knew about him came from my mother's stories, which I eagerly listened to instead of bedtime tales. I always loved music, so at 16, I joined an underground brass band. Our teacher taught us both the songs banned by the Soviet authorities and polkas or waltzes to divert suspicion. In 1968, spies stumbled upon our rehearsal, and we played Runov's waltz for them. They began dancing enthusiastically, so we played a second piece. They kept dancing and said, 'You play so well! You should make a living from this.' That's how we avoided problems."

In 1970, for refusing to cooperate with the KGB, Livyi was sent to a labor camp for 3 years.

In 1974, Vasyl returned to Ukraine. In March 2022, Vasyl died.

In the spring of 1951, MGB officers took 7-month-old Livyi and his family from the village of Pidhirtsi, Ukraine, to Siberia. He was transported for 2 weeks by boxwagon to the village of Tsentralnyy Khazan, Irkutsk region. "During the journey, my mother fed me chicory because there was no milk."

A year after arriving in Siberia, his father was arrested as an ideological opponent and given 25 years of imprisonment. His mother was left without a husband and with three children. "For the first 5 years, I had no idea what my father looked like; I had never even seen a photograph of him. Everything I knew about him came from my mother's stories, which I eagerly listened to instead of bedtime tales. I always loved music, so at 16, I joined an underground brass band. Our teacher taught us both the songs banned by the Soviet authorities and polkas or waltzes to divert suspicion. In 1968, spies stumbled upon our rehearsal, and we played Runov's waltz for them. They began dancing enthusiastically, so we played a second piece. They kept dancing and said, 'You play so well! You should make a living from this.' That's how we avoided problems."

In 1970, for refusing to cooperate with the KGB, Livyi was sent to a labor camp for 3 years.

In 1974, Vasyl returned to Ukraine. In March 2022, Vasyl died.

Vasyl Bordyuzhenko (87), shows his hands with two fingers missing from his right hand, which he lost as a teenager due to labor exploitation in Siberia.

At 3 in the morning, armed Soviet soldiers woke up the Bordyuzhenko family and their four children, informing them of forced exile with property confiscation. "We were allowed only to dress, nothing more. My mother took a blanket to wrap the youngest brother, who was 2 months old. I was 14 at the time."

The family was loaded into a small сargo wagon, where over 40 people were crammed. "People were packed like sardines. There were not enough seats for everyone, so the men traveled standing for 3 weeks." After reaching Ufa, which was 2500 km away, Vasyl's younger brother almost died of hunger because their mother lost her breast milk. "She started shouting through the bars of the wagon to the guards, 'My child is dying of hunger, give her food, otherwise I will throw the child out of the window because I don't want to see her die in my arms.' At the next stop, the guards issued a child's ration."

Once a day, they ate dry rations and moistened their lips with rainwater collected from the roof of the wagon during the journey. They were brought to the Alzamay station in the Irkutsk region, where they were forced to stand in the freezing cold with snow up to their knees for three days under armed guard. After that, they were taken deep into the taiga, where they had to build primitive shelters from larch bark to live in. "In the first year of exile, there was a flu epidemic in our settlement, and about 6 families died due to lack of medicine.

Food was in short supply, I felt constant hunger. My lunch consisted of a cube of sugar and river water. To help the family, I went to work. We were brutally exploited at work in the forest, paid only with food. As a minor, I was assigned to work as an assistant to a tractor driver in the logging camp, and during the night shift, due to the lack of protective equipment on the tractor, I lost two fingers of my right hand. It was -45 degrees Celsius. Before we reached home, which was 5 km away, blood dripped onto the floor of the tractor and froze the size of a hat. Despite bleeding profusely, I received the necessary medical assistance only after 12 hours.

It was hazardous to work in the forest, at least 5 young men died, and one of my friends was torn apart."

In 1969, Bordyuzhenko was able to return from exile to Ukraine.

Fedir Hutnyk (91), poses in the atmosphere of her memories in her home in Ivano-Frankivsk.

Around 7:00 in the morning, the head of the village council and military personnel appeared in Gutnyk's yard. "I wasn't allowed to get out of bed, and they began questioning my mother. We were given one hour to gather the necessary belongings. We didn't know where they were taking us. The сargo wagon was very dirty, and there was a severe lack of air. Throughout the entire journey, we were only given food twice: 2 buckets of boiled water and 4 loaves of bread for 28 people; thirst tormented us incredibly. There was a foul corpse odor in the wagon because three people had died, and their bodies were with us until the military threw them out onto the tracks without burial at one of the stations."

On the second day after arriving in Siberia, 18-year-old Gutnyk was taken for hard labor in logging. "I was working without days off, seven days a week. One day, I ended up in the hospital with a concussion from a branch falling on my head. Two of my coworkers died in similar accidents."

In the third year of exile, Gutnyk was handed a conscription notice despite already being under a form of imprisonment, and prisoners were not subject to the draft. "I refused on grounds of conscience freedom and was beaten by a representative of the special commission. I left the office covered in blood. The KGB repeatedly tried to force me to sign a letter renouncing my faith in God in exchange for returning to Ukraine."

In 1973, Gutnik was able to return from exile to Ukraine.

On the second day after arriving in Siberia, 18-year-old Gutnyk was taken for hard labor in logging. "I was working without days off, seven days a week. One day, I ended up in the hospital with a concussion from a branch falling on my head. Two of my coworkers died in similar accidents."

In the third year of exile, Gutnyk was handed a conscription notice despite already being under a form of imprisonment, and prisoners were not subject to the draft. "I refused on grounds of conscience freedom and was beaten by a representative of the special commission. I left the office covered in blood. The KGB repeatedly tried to force me to sign a letter renouncing my faith in God in exchange for returning to Ukraine."

In 1973, Gutnik was able to return from exile to Ukraine.

Ivan Pankiv (80),

Ivan's father was imprisoned in the Karaganda correctional labor camp for his religious stance in 1945. On the morning of April 8, 1951, a vehicle arrived at the Pankiv family's home. They were issued a protocol and told to gather their belongings because they were being deported to Siberia. "Our cow, pigs, and all our belongings were confiscated, and joined the collective farm. I, at the age of 6, along with four family members, were repressed." In Siberia, Ivan hardly attended first grade due to frequent illnesses from exposure to the harsh climate. "My ears and teeth often ached due to the severe cold. In school, local children mocked me and stole my personal belongings. My older brother's daughter was born, and she caught a cold and got sick with whooping cough and died, there was no medicine in our settlement.

The daughter of our friends was imprisoned for answering a direct question from local authorities about why they were repressed: "For faith in God." In the place of imprisonment, she was tortured with electric shock, which drove her insane, and she died in Siberia at a young age."

In 1966, Pankiv was able to return from exile to Ukraine.

The daughter of our friends was imprisoned for answering a direct question from local authorities about why they were repressed: "For faith in God." In the place of imprisonment, she was tortured with electric shock, which drove her insane, and she died in Siberia at a young age."

In 1966, Pankiv was able to return from exile to Ukraine.

Halyna Basumak (73), holds one of the few photos from Siberia, where she is 3 years old with her parents and brother next to their first cow. The cow was sick with brucellosis. Despite this, due to difficult circumstances and the threat of starvation, the family consumed the sick cow's scalded milk. However, they had to slaughter and bury her, and the Basumak family didn't eat the meat either. Behind her, a blanket, the only thing left from the house before the exile to Siberia.

11-month-old Basumak and her family were deported from Lviv to Siberia. The soldiers treated them kindly; they collected all their property, which Basumak's mother exchanged for food upon arrival.

During the two-week trip, the convoys did not give food to the child. Basumak was starving all the way. "My mother was convinced that I would die because I didn't even have the strength to cry." They were brought to the Bilyolik farm (Republic of Khakassia), to a settlement to work on the farm. Basumak recalls: “There were no clothes, but I grew up. We wrapped rags around our legs and put on fable trousers on top. My greatest fear was that my mother would die. She had a heart defect, and in Siberia, the climate made her condition worse."

In 1967 she returned to Ukraine. After the collapse of the USSR, she received a rehabilitation certificate as a victim of repression.

11-month-old Basumak and her family were deported from Lviv to Siberia. The soldiers treated them kindly; they collected all their property, which Basumak's mother exchanged for food upon arrival.

During the two-week trip, the convoys did not give food to the child. Basumak was starving all the way. "My mother was convinced that I would die because I didn't even have the strength to cry." They were brought to the Bilyolik farm (Republic of Khakassia), to a settlement to work on the farm. Basumak recalls: “There were no clothes, but I grew up. We wrapped rags around our legs and put on fable trousers on top. My greatest fear was that my mother would die. She had a heart defect, and in Siberia, the climate made her condition worse."

In 1967 she returned to Ukraine. After the collapse of the USSR, she received a rehabilitation certificate as a victim of repression.

Petro Chekhovskyi (86), in his house, Svarychiv, Ukraine poses for a photograph just as he did in 1955 after his arrest by the KGB.

In 1955, as a result of a special operation, the KGB intercepted Chekhovskyi and imprisoned him for 10 months in solitary confinement where he was subjected to psychological methods of pressure. Their keen interest in Chekhovskyi was due to his special responsibilities in the then-banned organization of Jehovah's Witnesses.

"Ten KGB officers pulled me out of a public bus, forcibly dragged me into their car, dressed me in a military coat and a KGB cap, and took me for interrogation at the KGB office.There, I refused to eat for five days because I thought they would put something in the food to make me talk. Then I was transferred to the Kyiv pre-trial detention center, where they locked me in a cell with a metal chair embedded in the floor. The investigator said, "Burak sat in that chair," my friend who had been tortured to death earlier. I thought "it would be tough". Interrogations could start during the day and last until night. I had information about the activities of Jehovah's Witnesses in the USSR, the names of all key figures, the number of convicted individuals... and I submitted reports through a secret emissary. They told me, 'How is this not espionage work, for America to know how many camps we have here!?' They scalded me with boiling water in the shower, and in the cell, they forbade me from sleeping on my side, so the light bulb constantly shone into my eyes, preventing me from sleeping." He did not break, so he was sentenced to 8 years in the Mordovian Gulag.

"Ten KGB officers pulled me out of a public bus, forcibly dragged me into their car, dressed me in a military coat and a KGB cap, and took me for interrogation at the KGB office.There, I refused to eat for five days because I thought they would put something in the food to make me talk. Then I was transferred to the Kyiv pre-trial detention center, where they locked me in a cell with a metal chair embedded in the floor. The investigator said, "Burak sat in that chair," my friend who had been tortured to death earlier. I thought "it would be tough". Interrogations could start during the day and last until night. I had information about the activities of Jehovah's Witnesses in the USSR, the names of all key figures, the number of convicted individuals... and I submitted reports through a secret emissary. They told me, 'How is this not espionage work, for America to know how many camps we have here!?' They scalded me with boiling water in the shower, and in the cell, they forbade me from sleeping on my side, so the light bulb constantly shone into my eyes, preventing me from sleeping." He did not break, so he was sentenced to 8 years in the Mordovian Gulag.

Until 1991, the Soviet secret services regularly summoned him for questioning. For unknown reasons, Chekhovskyi escaped exile in Siberia in 1951.

In 2020, research revealed that this story of the KGB special operation formed the basis of an exposition of an atheist museum in the Soviet Union, which included a photograph of prisoner Chekhovskyi, a bunker, publications, and all materials related to the underground.

In 2020, research revealed that this story of the KGB special operation formed the basis of an exposition of an atheist museum in the Soviet Union, which included a photograph of prisoner Chekhovskyi, a bunker, publications, and all materials related to the underground.

Vasyl Kochergan (86), in his home in the Carpathians, poses in a Siberian sweatshirt that he wore while working in exile, against the backdrop of a carpet from his ethnic people.

Around midnight armed soldiers entered the Kochergan dwelling and presented the head of the family with a document renouncing their faith in exchange for avoiding repression. "Father read the document and said he wouldn't renounce Jehovah God." Previously, his comrades and fellow believers were tortured to death by sadistic methods for the same stance, their bodies thrown into ditches. Another relative was executed.

"The journey to Siberia took 17 days. There were no toilets, we had to relieve ourselves in a bucket. In Siberia warden, who constantly watched over us, forced me, a 12-year-old, to work in the forest. I worked six days a week for eight hours each day. Working in the winter, especially in 57-degree frost, was the hardest."

Two Vasyl friends were forcibly taken by the KGB to a psychiatric hospital and held for a month, where they were subjected to medical experiments. Unfortunately, one of them lost his mind. Their belief in God was the pretext for such cruelty.

"At the age of 24, when my son was born, I was imprisoned for refusing military service on conscientious grounds. During the investigation, I was threatened that I would either die young in the camp or become disabled. The investigator pointed a gun at me and threatened, "I'll shoot you, and I have the right to do so because you're a traitor, and I won't face any consequences." Additionally, I was constantly offered freedom in exchange for renouncing my beliefs."

"The journey to Siberia took 17 days. There were no toilets, we had to relieve ourselves in a bucket. In Siberia warden, who constantly watched over us, forced me, a 12-year-old, to work in the forest. I worked six days a week for eight hours each day. Working in the winter, especially in 57-degree frost, was the hardest."

Two Vasyl friends were forcibly taken by the KGB to a psychiatric hospital and held for a month, where they were subjected to medical experiments. Unfortunately, one of them lost his mind. Their belief in God was the pretext for such cruelty.

"At the age of 24, when my son was born, I was imprisoned for refusing military service on conscientious grounds. During the investigation, I was threatened that I would either die young in the camp or become disabled. The investigator pointed a gun at me and threatened, "I'll shoot you, and I have the right to do so because you're a traitor, and I won't face any consequences." Additionally, I was constantly offered freedom in exchange for renouncing my beliefs."

Volodymyr Hnativ (73), holds a photo of his Siberian childhood, where he is 3 years old.

Hnat's mother was pregnant with him when she left Ukraine for Siberia in 1951. He was born in barracks in Vynogradovsk, Irkutsk region. Today Hnativ recalls: “We didn't have a cow, and we lived in extreme poverty. My mother didn't have breast milk, so the first three years were tough. I survived on Siberian teas. Because of this, I still have problems with my digestive system due to my hungry childhood. The most difficult years of my childhood were the years in a boarding school, where there were mostly children from disadvantaged families. I was forced to live and study there to get at least some education. It was a real children's prison.” There he was bullied by other children; his peers set his feet on fire, poured cold water on him, beat him, and mocked him in every possible way.

In 1966, Gnativ returned to Ukraine with his parents.

Hnat's mother was pregnant with him when she left Ukraine for Siberia in 1951. He was born in barracks in Vynogradovsk, Irkutsk region. Today Hnativ recalls: “We didn't have a cow, and we lived in extreme poverty. My mother didn't have breast milk, so the first three years were tough. I survived on Siberian teas. Because of this, I still have problems with my digestive system due to my hungry childhood. The most difficult years of my childhood were the years in a boarding school, where there were mostly children from disadvantaged families. I was forced to live and study there to get at least some education. It was a real children's prison.” There he was bullied by other children; his peers set his feet on fire, poured cold water on him, beat him, and mocked him in every possible way.

In 1966, Gnativ returned to Ukraine with his parents.

Pavlina Proskyrnyk (81), poses in her home in Prykarpattia against the backdrop of an ethnic Carpathian rug.

At night, soldiers came to the Proskyrnyk family's home, lined up the parents and their three young children against the wall, and read the verdict: "Deporte to Siberia." Proskyrnyk was 9 years old at the time.

"There were 40 people in the сargo wagon. We traveled for a week, and then one woman went into labor. The women helped with the delivery, and a baby boy was born. There was a small window high up on the wall of the wagon."

They were brought to Kvitok. On the platform, so-called traders selected labor force. Those who looked better and without defects got to work at the factory. The weaker or older ones were sent to work in the forest in taiga, which was a worse job. We were lucky because we were chosen for the furniture factory, as my father was a cartwright. In the winter, it was so cold in the barracks that water froze in the bucket and couldn't be broken through. The commandant's regime did not allow us to leave the settlement beyond 2 km."

At 15, Proskoornyk went to work. "From the first day, I was assigned to the circular saw. It was very dangerous work; my partner, who worked with me at the machine, lost three fingers." In 1961, Proskyrnyk's husband was imprisoned. "At that time, I gave birth to our first child."

The authorities tried to deprive Pavlina and her husband of their parental rights over their four children, citing the anti-Soviet upbringing of the children as the reason.

"There were 40 people in the сargo wagon. We traveled for a week, and then one woman went into labor. The women helped with the delivery, and a baby boy was born. There was a small window high up on the wall of the wagon."

They were brought to Kvitok. On the platform, so-called traders selected labor force. Those who looked better and without defects got to work at the factory. The weaker or older ones were sent to work in the forest in taiga, which was a worse job. We were lucky because we were chosen for the furniture factory, as my father was a cartwright. In the winter, it was so cold in the barracks that water froze in the bucket and couldn't be broken through. The commandant's regime did not allow us to leave the settlement beyond 2 km."

At 15, Proskoornyk went to work. "From the first day, I was assigned to the circular saw. It was very dangerous work; my partner, who worked with me at the machine, lost three fingers." In 1961, Proskyrnyk's husband was imprisoned. "At that time, I gave birth to our first child."

The authorities tried to deprive Pavlina and her husband of their parental rights over their four children, citing the anti-Soviet upbringing of the children as the reason.

Teodoziia Sabat (78), is sitting on a Polish chest in which her mother was packing things before being taken to Siberia, her mother's Siberian valenki felt boots are standing next to her.

Sabat was 5 years old, when they were taken to Siberia from the town of Skole in the Carpathian Beskids, Ukraine. Today she remembers that for her, as a child, the road was fun. After two weeks of travel in a boxwagon, they were brought to work in the area of Molta, Irkutsk region.

Sabat spent 9 years in exile. After the collapse of the USSR, she received a rehabilitation certificate as a victim of repression.

Sabat was 5 years old, when they were taken to Siberia from the town of Skole in the Carpathian Beskids, Ukraine. Today she remembers that for her, as a child, the road was fun. After two weeks of travel in a boxwagon, they were brought to work in the area of Molta, Irkutsk region.

Sabat spent 9 years in exile. After the collapse of the USSR, she received a rehabilitation certificate as a victim of repression.

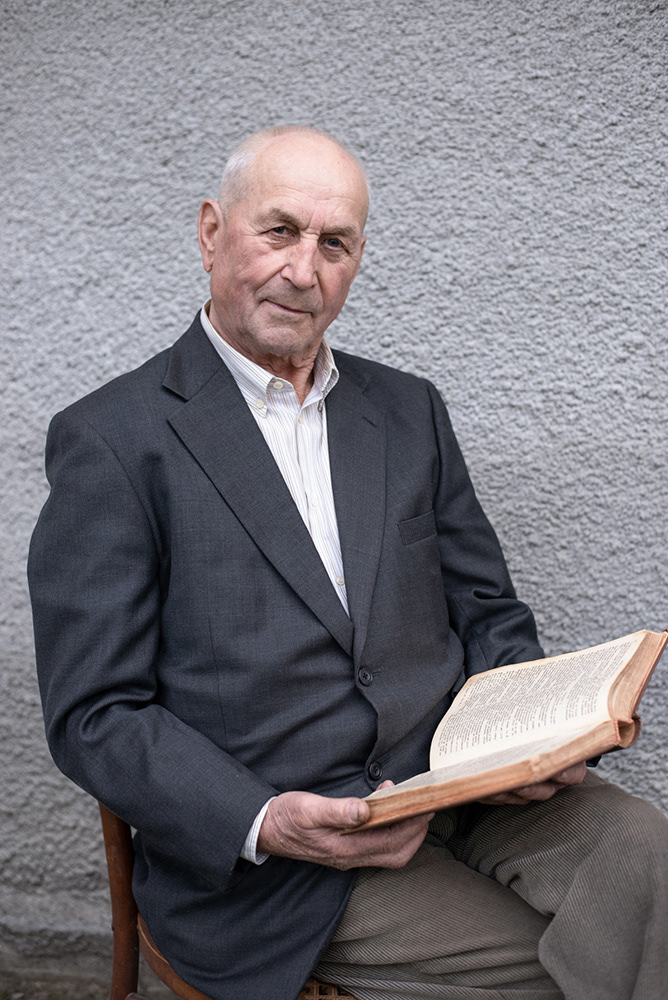

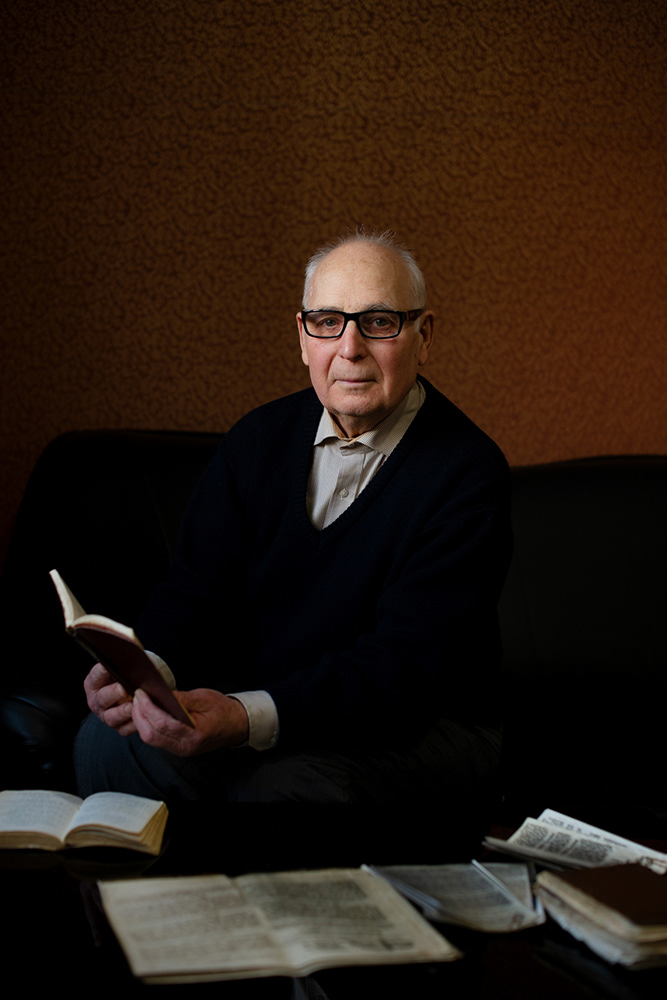

Ivan Pylypiv (87), is holding a family relic, a Bible from 1930, successfully saved from the confiscation of MGB employees during the exile to Siberia.

At the age of 14, Pylypiv and his parents were deported from the village of Hrabiv in the Carpathians. At the railway station in Krekhovychi, they were put in the first boxcar of the echelon, so the travel to Siberia lasted a whole month. They were fed only once a day, so due to severe malnutrition, Pylypiv stopped seeing well. "After arriving, we were transferred to sleds, and for 18 kilometers, tamed wild horses pulled us along the Oka River. The huge ice chunks and cracks that the horse leaped over were so wide that at one point, the horse couldn’t jump over one and fell into the water, hanging from the shafts! People managed to pull him out, and that horse, with its hooves battered, pulled the sleds to the village of Yermakovka." Despite very poor eyesight, Pylypiv was forced to go to work in the woods: "It was slave exploitation of children because we were not paid anything."

In 1971, Soviet television in Siberia forced Ivan Pylypiv's family to give interviews in order to ridicule their position in life and, based on their answers, to strip them of their parental rights over their two daughters, who were in 2nd and 4th grade at the time.

Pylypiv spent 21 years in Siberia, and in 1972 he returned to Ukraine. After the collapse of the USSR, he received a rehabilitation certificate as a victim of repression.

At the age of 14, Pylypiv and his parents were deported from the village of Hrabiv in the Carpathians. At the railway station in Krekhovychi, they were put in the first boxcar of the echelon, so the travel to Siberia lasted a whole month. They were fed only once a day, so due to severe malnutrition, Pylypiv stopped seeing well. "After arriving, we were transferred to sleds, and for 18 kilometers, tamed wild horses pulled us along the Oka River. The huge ice chunks and cracks that the horse leaped over were so wide that at one point, the horse couldn’t jump over one and fell into the water, hanging from the shafts! People managed to pull him out, and that horse, with its hooves battered, pulled the sleds to the village of Yermakovka." Despite very poor eyesight, Pylypiv was forced to go to work in the woods: "It was slave exploitation of children because we were not paid anything."

In 1971, Soviet television in Siberia forced Ivan Pylypiv's family to give interviews in order to ridicule their position in life and, based on their answers, to strip them of their parental rights over their two daughters, who were in 2nd and 4th grade at the time.

Pylypiv spent 21 years in Siberia, and in 1972 he returned to Ukraine. After the collapse of the USSR, he received a rehabilitation certificate as a victim of repression.

Anton Zadorozhnyi (84), holds a German Barcarole accordion, which he managed to buy during his exile to Siberia.

The night of April 8, 1951, Zadorozhnyi, who was 10, recalls in these words: "The first words I heard that night were, 'Children get up; we will go to Siberia.' We were given 2 hours to gather. What could we collect during this time? Nothing". He and his mother and sister were deported from the village of Ustya, Ukraine, to the town of Zima in the Irkutsk region of Russia. Zadorozhnyi recalls: "Shortly before leaving, the family learned that we were being taken to Siberia, so they ran to the platform in Rozvadiv, where we were already loaded into cattle wagons, and they began to throw bread at us through the windows for our way."

In the 1960s, Zadorozhnyi organized an underground choir, in which he, as a choirmaster, taught singing religious songs banned by the Soviet Union. He was threatened with imprisonment for such activities.

In 1964 Zadorozhnyi returned to Ukraine.

The night of April 8, 1951, Zadorozhnyi, who was 10, recalls in these words: "The first words I heard that night were, 'Children get up; we will go to Siberia.' We were given 2 hours to gather. What could we collect during this time? Nothing". He and his mother and sister were deported from the village of Ustya, Ukraine, to the town of Zima in the Irkutsk region of Russia. Zadorozhnyi recalls: "Shortly before leaving, the family learned that we were being taken to Siberia, so they ran to the platform in Rozvadiv, where we were already loaded into cattle wagons, and they began to throw bread at us through the windows for our way."

In the 1960s, Zadorozhnyi organized an underground choir, in which he, as a choirmaster, taught singing religious songs banned by the Soviet Union. He was threatened with imprisonment for such activities.

In 1964 Zadorozhnyi returned to Ukraine.

Oksana Mostovyk (78), recounts that in 1949 a police officer broke into their house in the village of Markivtsi, Ukraine: "He aggressively lines up my widowed mother and us four children in a row. He points a gun at her throat and says, 'I will shoot you all right here!' I, a four-year-old child, step in to protect her." After that, her mother was sentenced to 10 years in a Khabarovsk camp for her neutral position on political issues. "After trial, I ran up and gave her the bun, but the guard hit her hand so hard that the bun flew out and rolled down the stairs. I started crying, but my mom cheerfully said, 'Children, don't cry, I'm happy to see you because during the interrogation they told me that all of you had been shot!"

At the age of 5, Mostovyk, along with her two older sisters and brother, was deported to the settlement Veselyi, Siberia. "We were transported on sleds across the Chuna River on already melting ice. The ice was cracking and breaking apart, and there were already thawed holes. I was put on a sled with neighbors. Later, I moved to the sled with my sister. This saved my life because shortly after, the sled with the neighbors fell through the ice. They were all rescued."

In 1956, Mostovyk's mother received an early release from the camp. Mostovyk recalls: "I knew it was my mother, but I didn't have affection for her, I couldn't get used to her and call her 'mother' for a long time."

She spent 14 years in exile and 1968 she returned to Ukraine.

At the age of 5, Mostovyk, along with her two older sisters and brother, was deported to the settlement Veselyi, Siberia. "We were transported on sleds across the Chuna River on already melting ice. The ice was cracking and breaking apart, and there were already thawed holes. I was put on a sled with neighbors. Later, I moved to the sled with my sister. This saved my life because shortly after, the sled with the neighbors fell through the ice. They were all rescued."

In 1956, Mostovyk's mother received an early release from the camp. Mostovyk recalls: "I knew it was my mother, but I didn't have affection for her, I couldn't get used to her and call her 'mother' for a long time."

She spent 14 years in exile and 1968 she returned to Ukraine.

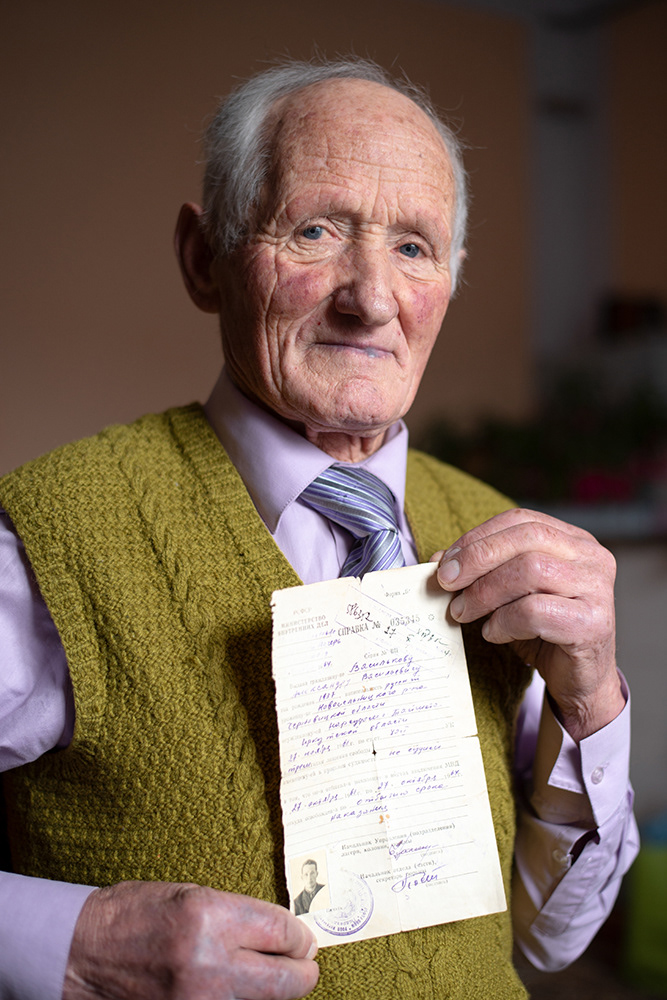

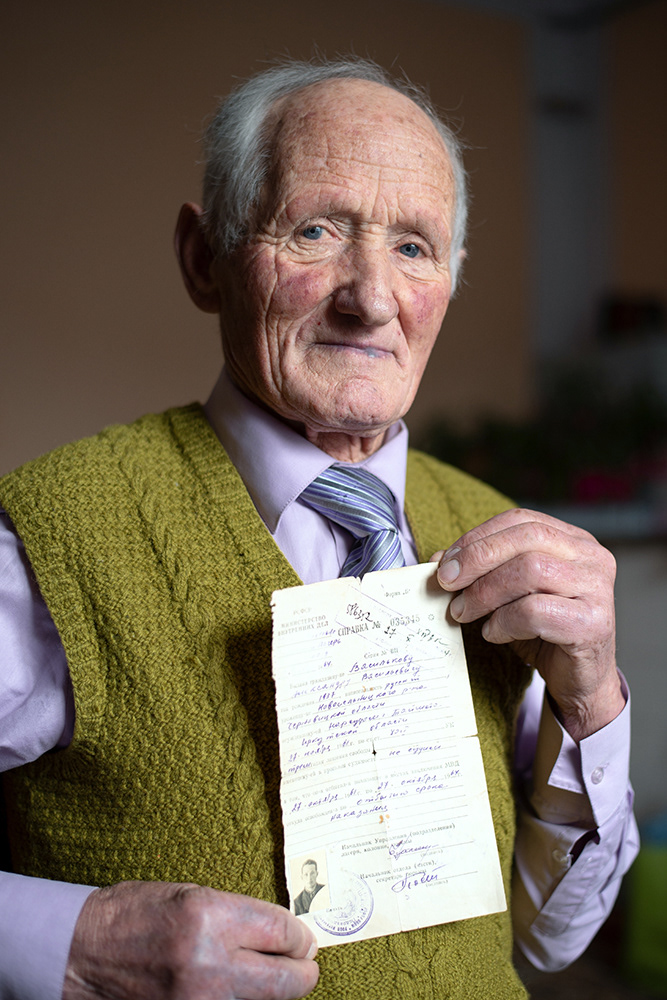

Oleksandr Vasylkov (87), holds a certificate from the Ministry of Internal Affairs on his release from the Ust-Kut correctional labor camp.

As a child, Vasylkov experienced a great famine in the USSR in 1946 and 1947, during which almost 1.5 million people died. "They took our grain; it was a manmade famine. I saw people swelling from hunger and dying."

14-year-old Vasylkov from Synzher, Ukraine, was exiled to Siberia with his family. "When the soldiers were in my house, I jumped out the window, and they shouted, 'Stop, or I'll shoot!' and fired a burst into the air. Eventually, I got tangled in barbed wire. I was scared that the famine would happen again, so I ran away." Because of his escape attempt, the family wasn't allowed to take anything with them, so Vasylkov went to Siberia barefoot. He made another unsuccessful escape attempt at the station. In their carriage, about 80 people were cramped for 24 days, and two died along the way.

In Siberia, the family was settled in a barrack where it was so cold in winter that "hair would freeze to the iron bed." About his work, Vasylkov says, "Every year, 2-3 men would die. A log crushed my relative's head."

In 1961, Oleksandr was sentenced to five years in a labor camp for refusing military service.

"During the investigation, the KGB officer offered me to sign a document renouncing my faith in exchange for freedom. I told him, 'I cannot renounce God.' Later in the camp, they offered early release if I admitted my guilt and renounced my faith."

As a child, Vasylkov experienced a great famine in the USSR in 1946 and 1947, during which almost 1.5 million people died. "They took our grain; it was a manmade famine. I saw people swelling from hunger and dying."

14-year-old Vasylkov from Synzher, Ukraine, was exiled to Siberia with his family. "When the soldiers were in my house, I jumped out the window, and they shouted, 'Stop, or I'll shoot!' and fired a burst into the air. Eventually, I got tangled in barbed wire. I was scared that the famine would happen again, so I ran away." Because of his escape attempt, the family wasn't allowed to take anything with them, so Vasylkov went to Siberia barefoot. He made another unsuccessful escape attempt at the station. In their carriage, about 80 people were cramped for 24 days, and two died along the way.

In Siberia, the family was settled in a barrack where it was so cold in winter that "hair would freeze to the iron bed." About his work, Vasylkov says, "Every year, 2-3 men would die. A log crushed my relative's head."

In 1961, Oleksandr was sentenced to five years in a labor camp for refusing military service.

"During the investigation, the KGB officer offered me to sign a document renouncing my faith in exchange for freedom. I told him, 'I cannot renounce God.' Later in the camp, they offered early release if I admitted my guilt and renounced my faith."

Myroslava Starunchak (74), was 11 months old when she, along with her family, was repressed to Siberia. In the fifth grade, Myroslava wrote a letter to Nikita Khrushchev, the then Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, in which she openly explained why their family was repressed to Siberia.

"Two years later, a response came from Moscow, stating that we were allowed to return home to Ukraine and return confiscated property. However, nothing was left of our former property".

In 1967 Starunchak returned to Ukraine.

Hanna Volosyanko (78), photographed at her home in the village of Staryi Lysets, from where she and her family were deported to Siberia.

Volosyanko was 5 years old when soldiers broke into their house. She says: “I wanted to be at home. When we were put on board the car, I broke free and started running around the car, shouting "I'm not going anywhere!" until two soldiers caught me. After 2 weeks of travel by box wagon, she and her family were brought to the village of Veselyi.

Volosyanko spent 14 years in exile and returned to Ukraine in 1966. After the collapse of the USSR, she received a rehabilitation certificate as a victim of repression.

Volosyanko was 5 years old when soldiers broke into their house. She says: “I wanted to be at home. When we were put on board the car, I broke free and started running around the car, shouting "I'm not going anywhere!" until two soldiers caught me. After 2 weeks of travel by box wagon, she and her family were brought to the village of Veselyi.

Volosyanko spent 14 years in exile and returned to Ukraine in 1966. After the collapse of the USSR, she received a rehabilitation certificate as a victim of repression.

Roman Vasiliev (85), photographed in his apartment in Ivano-Frankivsk, where he has been living since 2018 as a refugee after being forced to move from Russia due to the resumption of persecution of Jehovah's Witnesses in that country.

In 1944, his father, a Jehovah's Witness, was forcibly taken by Red Army soldiers during WWII.

In 1951, at the age of 12, Vasiliev with his mother was repressed from the village of Dovpotiv, Ukraine to Siberia. There they learned about the tragic story of his father's death. "In 1944, a Red Army officer lined up 26 Jehovah's Witnesses, including my father, in a field in front of soldiers. Holding a gun in his hand, the officer threatens, 'If you don't take up arms, I'll shoot you in 15 minutes.' Fifteen minutes pass and the officer asks, 'Will you take it?' 'No.' Then he shot my father in the head, and he fell backward into a pit. He was 30 years old. Next, a second man also firmly refuses; the executioner shoots him too. The third, an 18-year-old young man and the brother of the second, approaches. He shakes his head 'No' with his eyes closed, and the officer kills him as well. After which the soldiers intervened and the remaining 23 survived. One of them told us this story."

In 1958, Vasiliev was sentenced to five years in prison for refusing to participate in military service.After Roman's initial imprisonment, the Soviet government made three more attempts to incarcerate him, pursuing him until the collapse of the Soviet Union. In December 2024, Roman died.

In 1944, his father, a Jehovah's Witness, was forcibly taken by Red Army soldiers during WWII.

In 1951, at the age of 12, Vasiliev with his mother was repressed from the village of Dovpotiv, Ukraine to Siberia. There they learned about the tragic story of his father's death. "In 1944, a Red Army officer lined up 26 Jehovah's Witnesses, including my father, in a field in front of soldiers. Holding a gun in his hand, the officer threatens, 'If you don't take up arms, I'll shoot you in 15 minutes.' Fifteen minutes pass and the officer asks, 'Will you take it?' 'No.' Then he shot my father in the head, and he fell backward into a pit. He was 30 years old. Next, a second man also firmly refuses; the executioner shoots him too. The third, an 18-year-old young man and the brother of the second, approaches. He shakes his head 'No' with his eyes closed, and the officer kills him as well. After which the soldiers intervened and the remaining 23 survived. One of them told us this story."

In 1958, Vasiliev was sentenced to five years in prison for refusing to participate in military service.After Roman's initial imprisonment, the Soviet government made three more attempts to incarcerate him, pursuing him until the collapse of the Soviet Union. In December 2024, Roman died.

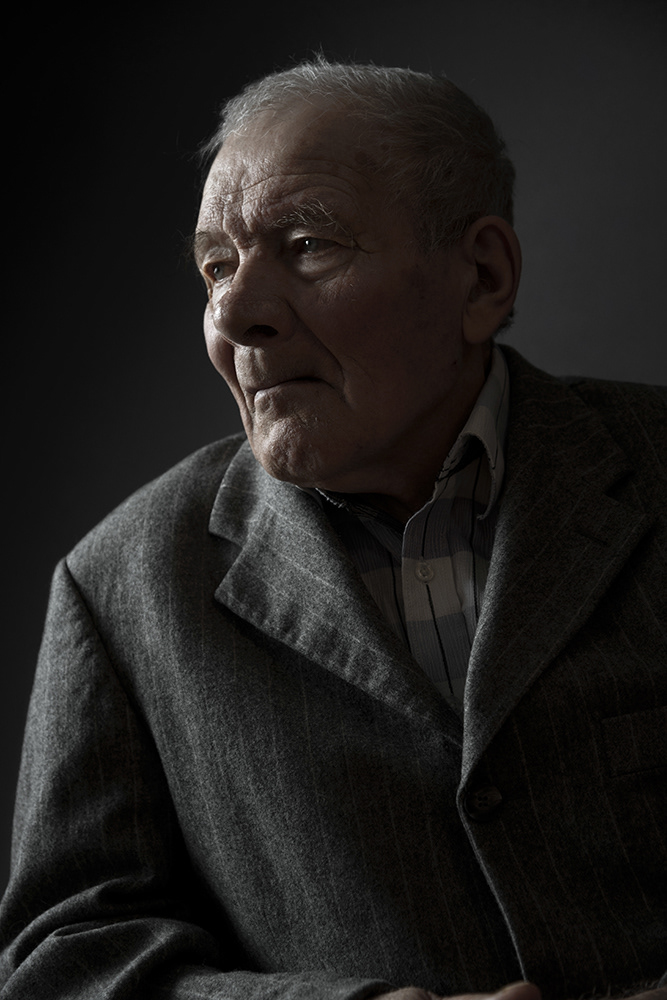

Leonid Vereshchynskyi (85), in the yard of his house, Stryi, Ukraine.

In 1951, Vereshchynskyi escaped exile to Siberia because his father was head of the village council. In 1955, 19-year-old Vereshchynskyi was sentenced by the Soviet authorities to 10 years in prison for refusing military service on the grounds of personal convictions: 5 years of hard labor and 5 years of exile, to which was added another 5 years of loss of rights. He says: "I clearly decided not to take part in any military conflicts and not even to learn it. In the military registration, I wrote a statement and explained why I was giving up military service and why I was convinced that it was necessary to solve problems humanely".

Prior to the announcement of Vereshchynskyi`s sentence, they forcibly detained him for 1 month, trying to break him emotionally, in the basement of the military registration and enlistment office in the village of Pidhaitsi (Ukraine). After the trial, he was immediately put in a boxcar with about 200 prisoners. Vereshchynskyi was taken to one of the Gulag's worst camps, Vorkutlag, during the coldest time of the year, where he worked in hard labor.

"We rode about 2 weeks to Vorkuta. On the way, I literally got frozen with clothes to the walls of the boxwagon, because there were about -50C outside.

During that trip at the stop, a chief came in and said: "Leonid Vereshchynskyi, is there one?" "I say, 'That's me.' – “Write two words that you renounce your faith, then we will transfer you to the oncoming train to Ukraine and you are free, you will go home”, I answer him, “Mr. chief, if I wanted to renounce my beliefs, I would do it at home”, at this point the dialogue ended.

In a prison camp, I used a pickaxe to dig up the permafrost land. If in one working day, 8 hours, I pulled out a handful of earth that fit in the palm of my hand, it was very good. The earth was like glass, the fragments of which were immediately dissected the skin".

It is estimated that in the repressive system of the Soviet Union, about 5 million people were imprisoned for political reasons. At least one million people were shot. The prisoners of such camps were Jehovah's Witnesses, people with the same convictions as Vereshchynskyi.

Prior to the announcement of Vereshchynskyi`s sentence, they forcibly detained him for 1 month, trying to break him emotionally, in the basement of the military registration and enlistment office in the village of Pidhaitsi (Ukraine). After the trial, he was immediately put in a boxcar with about 200 prisoners. Vereshchynskyi was taken to one of the Gulag's worst camps, Vorkutlag, during the coldest time of the year, where he worked in hard labor.

"We rode about 2 weeks to Vorkuta. On the way, I literally got frozen with clothes to the walls of the boxwagon, because there were about -50C outside.

During that trip at the stop, a chief came in and said: "Leonid Vereshchynskyi, is there one?" "I say, 'That's me.' – “Write two words that you renounce your faith, then we will transfer you to the oncoming train to Ukraine and you are free, you will go home”, I answer him, “Mr. chief, if I wanted to renounce my beliefs, I would do it at home”, at this point the dialogue ended.

In a prison camp, I used a pickaxe to dig up the permafrost land. If in one working day, 8 hours, I pulled out a handful of earth that fit in the palm of my hand, it was very good. The earth was like glass, the fragments of which were immediately dissected the skin".

It is estimated that in the repressive system of the Soviet Union, about 5 million people were imprisoned for political reasons. At least one million people were shot. The prisoners of such camps were Jehovah's Witnesses, people with the same convictions as Vereshchynskyi.

Volodymyr Yosyfiv (84), on April 8, 1951, at the age of 11, with his family, were deported from the village of Komariv, Ukraine. For 19 days they were transported in a freight car to the settlement of Izykan, Siberia.

"In the boxcar there was an unbearable smell of steam locomotive smoke mixed with feces". Once every few days, they were given a bucket of wheat porridge and a bucket of water to be distributed among more than 50 hungry people in their boxcar. For 12 years, Yosyfiv suffered from malnutrition and migraine and was diagnosed with anemia. "The commandant checked twice a day whether anyone had escaped. Our house was regularly searched for the presence of prohibited literature. The KGB set up a wiretap for espionage purposes and quoted our dialogues during interrogations."

In 1958, his letter to Khrushchev, a claim for persecution, was considered as a threat to the Secretary General, for which the KGB placed him in solitary confinement. "They put me in a filthy cell measuring 1.5 by 2.5 meters. At night, they frequently interrogated me, threatened me, and offered collaboration, which I refused. They said, 'You'll rot in prison, we'll give you 7 years.' After 10 days, they said, 'Considering your youth, we are releasing you.'"

Yosyfiv was deemed unfit for military service due to his health. After writing a letter to Khrushchev, his medical exemptions were annulled, and he was sentenced to 3 years in Siberian labor camps for refusing military service.

"In the boxcar there was an unbearable smell of steam locomotive smoke mixed with feces". Once every few days, they were given a bucket of wheat porridge and a bucket of water to be distributed among more than 50 hungry people in their boxcar. For 12 years, Yosyfiv suffered from malnutrition and migraine and was diagnosed with anemia. "The commandant checked twice a day whether anyone had escaped. Our house was regularly searched for the presence of prohibited literature. The KGB set up a wiretap for espionage purposes and quoted our dialogues during interrogations."

In 1958, his letter to Khrushchev, a claim for persecution, was considered as a threat to the Secretary General, for which the KGB placed him in solitary confinement. "They put me in a filthy cell measuring 1.5 by 2.5 meters. At night, they frequently interrogated me, threatened me, and offered collaboration, which I refused. They said, 'You'll rot in prison, we'll give you 7 years.' After 10 days, they said, 'Considering your youth, we are releasing you.'"

Yosyfiv was deemed unfit for military service due to his health. After writing a letter to Khrushchev, his medical exemptions were annulled, and he was sentenced to 3 years in Siberian labor camps for refusing military service.

In 1967 he returned to Ukraine

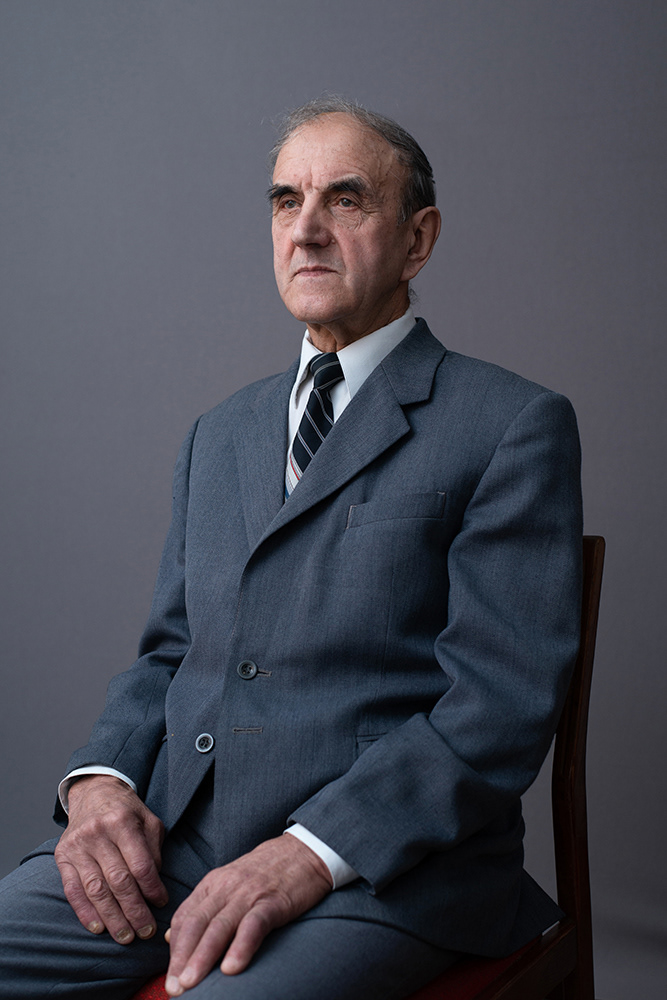

Volodymyr Krupianyk (86), is a veteran of the Ministry of Internal Affairs with the rank of lieutenant colonel, holding a photo from his service. Photographed in Rivne, Ukraine.

In 1964, Krupianyk became the head of the detachment of the correctional labor colony No.4 in the vicinity of Irkutsk. He said: “I have seen thousands of prisoners convicted of their crimes, including murderers and particularly dangerous recidivists. But there are five prisoners I will never forget”.

These five were Jehovah's Witnesses persecuted by the USSR for their beliefs. They had been repressed before Siberia years earlier.

Krupianyk was tasked by the KGB to re-educate such people by imposing communist propaganda upon them. He recalls: “I saw how honest these guys were, so I wondered why they were imprisoned and persecuted. I felt sorry for these guys because I understood that they were not guilty of anything.

Now I can say that it was very wrong to imprison and persecute people for their faith”.

In 1964, Krupianyk became the head of the detachment of the correctional labor colony No.4 in the vicinity of Irkutsk. He said: “I have seen thousands of prisoners convicted of their crimes, including murderers and particularly dangerous recidivists. But there are five prisoners I will never forget”.

These five were Jehovah's Witnesses persecuted by the USSR for their beliefs. They had been repressed before Siberia years earlier.

Krupianyk was tasked by the KGB to re-educate such people by imposing communist propaganda upon them. He recalls: “I saw how honest these guys were, so I wondered why they were imprisoned and persecuted. I felt sorry for these guys because I understood that they were not guilty of anything.

Now I can say that it was very wrong to imprison and persecute people for their faith”.

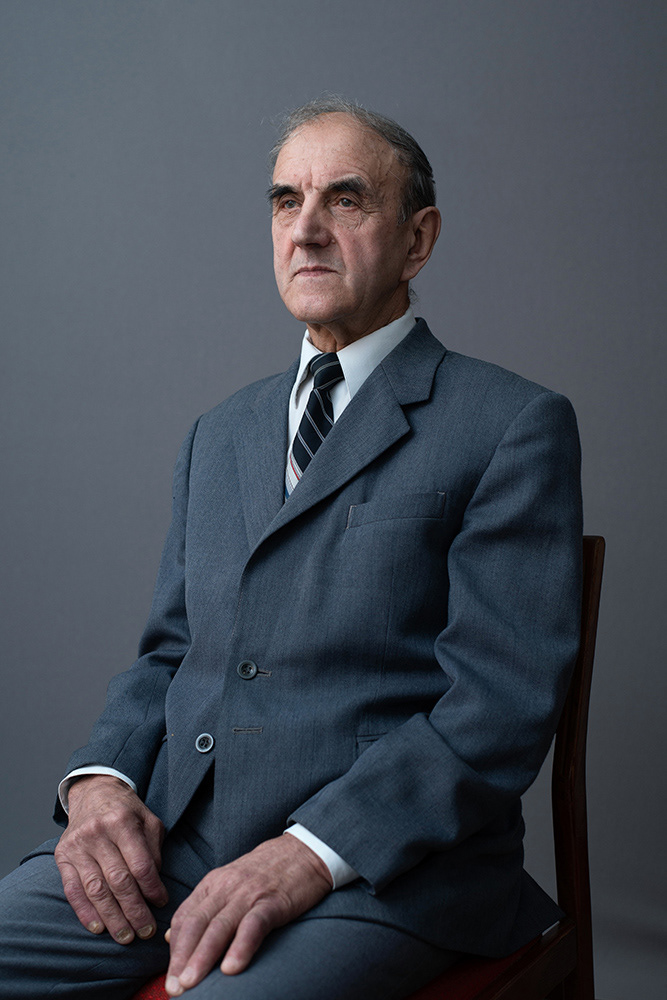

Volodymyr (69), a KGB counterintelligence officer from 1978 to 1991, photographed in his apartment, Ukraine.

The veteran says: "At that time, I did not know who Jehovah's Witnesses were because a separate 5th KGB department dealt with religious issues." When Volodymyr retired, he came across a book describing the events of the mass repression of Operation “North”. After reading this book, the veteran shares: “I had mixed feelings. At first, I was surprised by these people because under the pressure of trials, they were as hard as flint, and at the same time, I was filled with disgust for the system I served. After all, I was a patriot and believed in my cause, but at the same time I did not know that the KGB special services were persecuting innocent people.”

For security reasons, Volodymyr`s identity is hidden.

The veteran says: "At that time, I did not know who Jehovah's Witnesses were because a separate 5th KGB department dealt with religious issues." When Volodymyr retired, he came across a book describing the events of the mass repression of Operation “North”. After reading this book, the veteran shares: “I had mixed feelings. At first, I was surprised by these people because under the pressure of trials, they were as hard as flint, and at the same time, I was filled with disgust for the system I served. After all, I was a patriot and believed in my cause, but at the same time I did not know that the KGB special services were persecuting innocent people.”

For security reasons, Volodymyr`s identity is hidden.